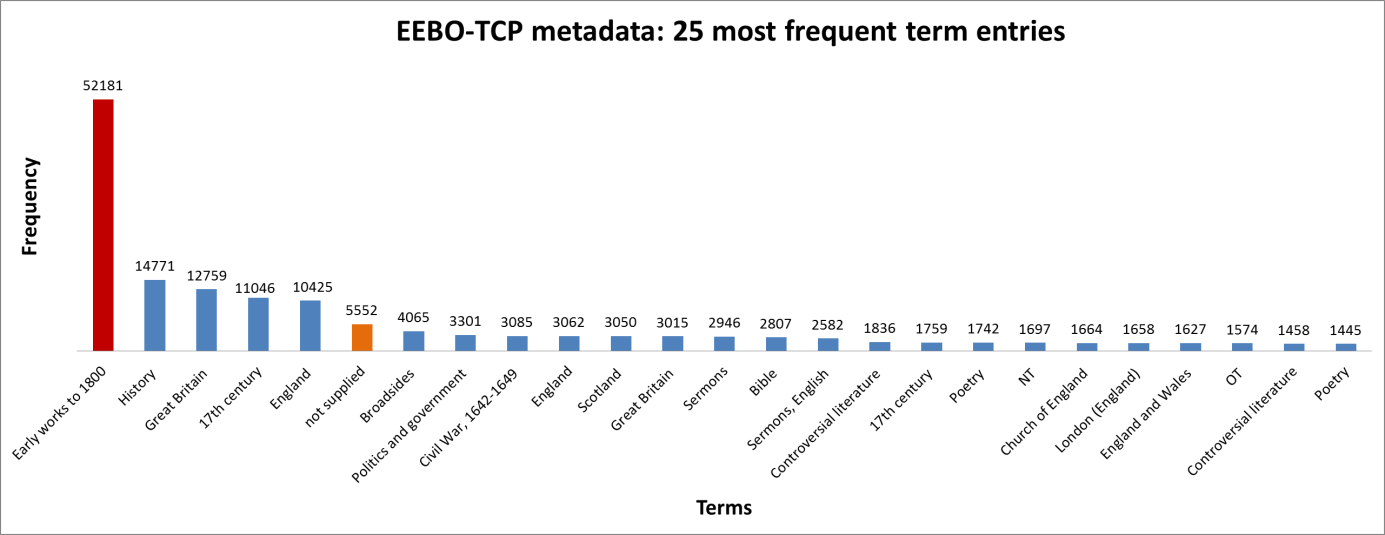

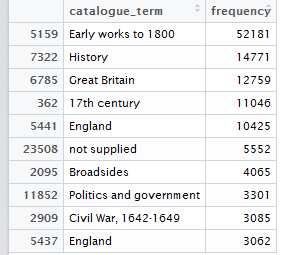

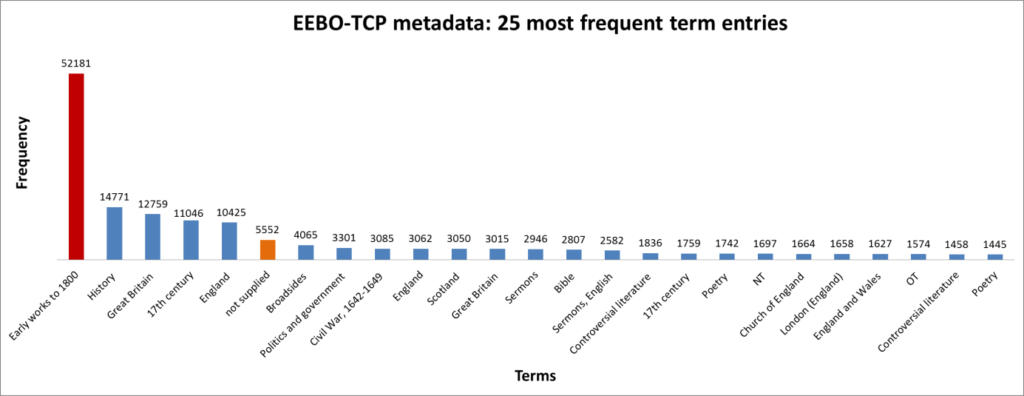

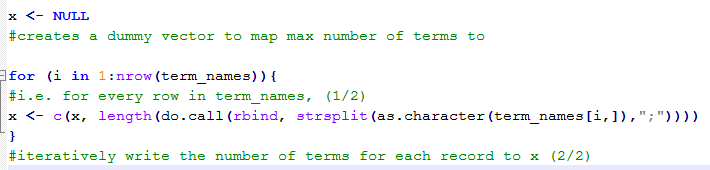

In Spring 2018, MA student Sophie Whittle dedicated 100 hours of hard graft to filling blanks in the Terms metadata. This work follows on from Winnie Smith’s work last year, identifying gaps in the Text Creation Partnership’s metadata. Sophie reflects on her experience and offers some tentative analysis focused on texts from the English Civil War and Commonwealth era:

As an MA linguistics student, I was elated to see an opportunity to apply for Linguistic DNA as part of the School of English’s work placement module. I am looking to apply for a PhD in the future, and I saw the project as a chance to undertake independent research. After completing a corpus-based dissertation about the semantic-syntactic development of the verb promise, I was looking forward to exploring historical texts in a different way—through the use of EEBO-TCP and LDNA computational methods.

After undertaking three years of linguistic study, I realised I had not delved into much historical work as my interests were very much theoretical at the time. Working on the placement has allowed me to regain historical interests which I had left back at GCSE and A-Level. During the summer prior to Masters study, I was in conversation about how King Charles I, who had intended to dine with the Governor of Hull (my home city) was stopped at Beverley Gate by Parliament. As the Governor had expressed allegiance to the Parliamentarians, he was named a traitor, but Charles was forced to return to York. This defining moment, not only for Hull but for Civil War history, piqued my interest. I was able to reflect on the conversation I’d had over summer whilst contributing to the inputting of empty metadata terms for LDNA and viewing documents of news and conflict from the Civil War. I wanted to understand the general public’s attitudes to the different sides of the Civil War in England by using LDNA’s conceptual modelling methods.

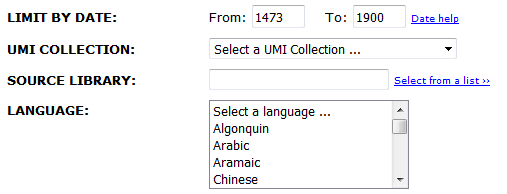

Towards the end of my placement, I wrote a proposal for a Civil War and Commonwealth collection to be included on the final LDNA interface. The large amount of texts from this period (a search via ProQuest’s EEBO interface (eebo.chadwyck.com) brings back 35,008 records) are of interest to researchers from linguistics, literature, history, theology, etc. Modelling concepts from and across the period, by determining frequently co-occurring words as pairs or trios, makes it clear that there is a wealth of information to research. My proposal employed the following term definitions:

Title contains: king

Terms contains: civil war, or commonwealth

Date range: 1642 to 1660

By defining these parameters, the idea was that a user could analyse attitudes towards different sides in the Civil War, from both Royalist and Parliamentarian perspectives.

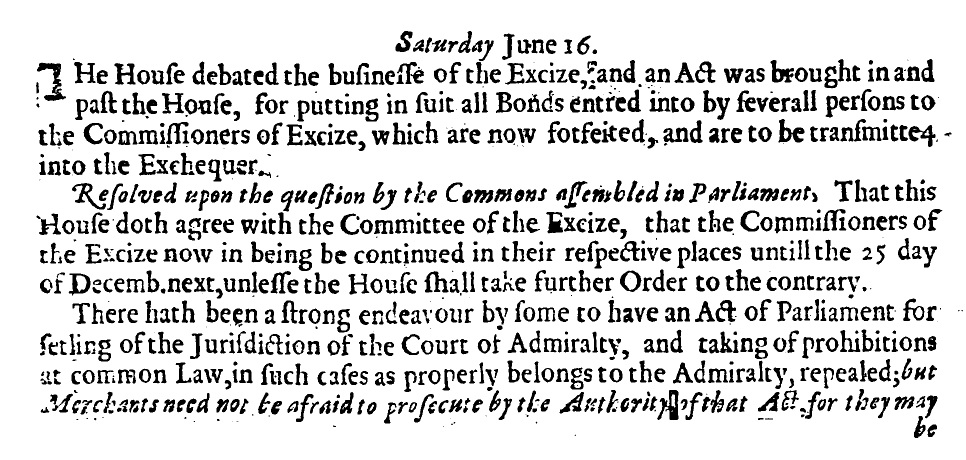

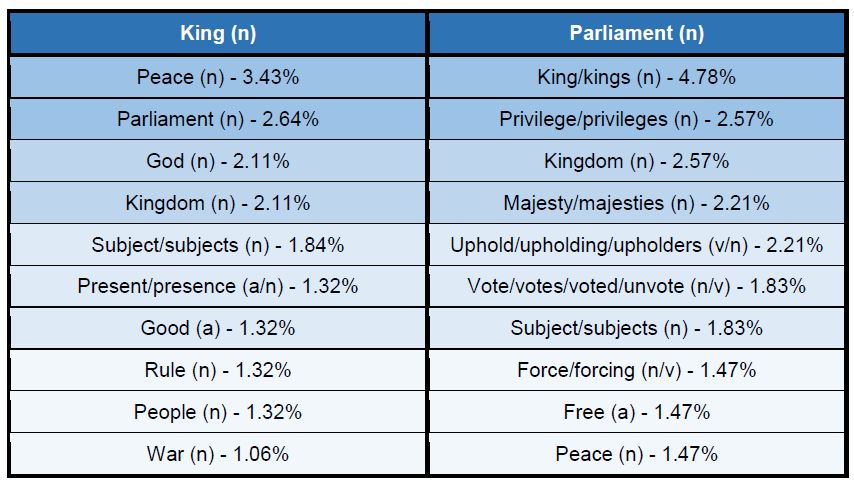

While designing my collection, I also wanted to see if I could mimic LDNA’s use of ‘windows’. I came across a four-text sample about the preserving of peace during the Civil War, with each text from different viewpoints. For instance, one of the texts discusses the New Model Army, a dissenting faction of the Parliamentarian side, as the ‘obstructors’ to peace in the kingdom (A25836). The army was largely independent and held radical Puritan views during the Civil War. Alternatively, a different text suggests peace was only possible if King Charles I prospered, rejecting Parliamentarianism (A25857). I used the node words ‘King’ and ‘Parliament’ as a starting point and counted ten words either side the node words (W20). I then calculated the frequency of the words with the most tokens, and came up with the following table (the frequency is displayed as a percentage):

Sampled cooccurrences with ‘king’ and ‘parliament’ for a window of 20 words.

The percentages are not particularly high (due to the size of the window, perhaps increasing the size of the window might help solve this issue). However, by identifying the ten most frequently co-occurring lemmas with the node words, a number of interesting results appear. For instance, peace co-occurs more frequently alongside King than Parliament, suggesting something about the bias of the texts. Further close-reading might indicate why peace was continuously associated with Royalism (or not, which emphasises the importance of close-reading!).

Additionally, the reason for vote co-occurring alongside Parliament might seem obvious at first. Yet analysing this within its context provides a different story. Most of the co-occurrences appear in the text slandering the New Model Army. In this text, the author believes that Parliament are voting in response to pressures from the NMA, and are therefore void of their privileges as a democratic union. A list of evidence is provided by the author to explain how Parliament have been revoked of their privileges (during the ‘tumult of the Apprentices’, when apprentices were freed from their masters and asked to join the NMA in ‘a state of confusion’). In the author’s view, the NMA forced Parliament to go against their morals by undoing their previous work.

I also gained access to trio output data from Susan and her work on Newsbooks, to see if I could find something similar. The top concepts for ‘King’ and ‘Parliament’ are ‘king – lord – parliament’ and ‘parliament – state – council’ respectively, which are expected from the genre of texts. By looking at slightly less frequent trios, there are some more intriguing items. The following trios complement the data I had found manually from the four-text sample: ‘king – people – liberty’ with a PMI of 3.09 and ‘parliament – present – authority’ with a PMI of 4.09. (Both PMIs show that the observed trios occur more often than expected by chance.) There is so much data to explore here, highlighting that LDNA should be an excellent resource for conducting quantitative study. As shown, it is important to analyse the findings within their contexts to specify how concepts are cemented in history. LDNA promote the combination of distant (using statistical methods) and close reading. It was interesting to imagine the final interface with the addition of literary analysis.

Working with the TCP metadata has allowed me to explore concepts within the Civil War and Commonwealth period and finalise the work placement by writing a collection brief. As a linguistics student, it has been a real challenge to identify texts based on their literary genre. This pushed me out of my comfort zone. Being able to use my semantic skills to pull apart the meaning behind the conceptual findings has helped too. I am very grateful to have been given the opportunity to use my existing skills and gain new ones!

Featured image: Hull City Skyline. From an original photograph by John Bannon. Used under license CC 3.0.