Ahead of the 2016 Sixteenth Century Conference, Linguistic DNA Research Associate Iona Hine reflected on the limits of what probing EEBO can teach us about sixteenth century English. This is the first of two posts addressing the common theme “What does EEBO represent?”

The 55 000 transcriptions that form EEBO-TCP are central to LDNA’s endeavour to study concepts and semantic change in early modern English. But do they really represent the “universe of English printed discourse”?

The easy answer is “no”. For several reasons:

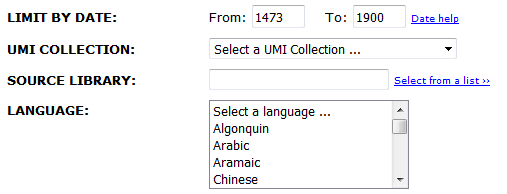

As is well documented elsewhere, EEBO is not restricted to English-language texts (cf. e.g. Gadd). Significant bodies of Latin and French documents printed in Britain have been transcribed, and one can browse through a list of other languages identified using ProQuest’s advanced search functionality. To this extent, EEBO represents more than the “universe of English printed discourse”.

But it also represents a limited “universe”. EEBO can only represent what survived to be catalogued. Its full image records represent individual copies. And its transcriptions represent a further subset of the survivals. As the RA currently occupied with reviewing Lost Books (eds. Bruni & Pettegree),* I have a keen awareness of the complex patterns of survival and loss. A prestigious reference work, the must-buy for ambitious libraries, might have a limited print run and yet was almost guaranteed survival–however much it was actively consulted. A popular textbook, priced for individual ownership, would have much higher rates of attrition: dog-eared, out-of-date, disposable. Survival favours genres, and there will be gaps in the English EEBO can represent.

The best function of the “universe” tagline is its emphasis on print. We have limited access to the oral cultures of the past, though as Cathy Shrank’s current project and the Corpus of English Dialogues demonstrate, there are constructions of orality within EEBO. Equally, where correspondence was set in print, correspondence forms a part of EEBO-TCP. There is diversity within EEBO, but it is an artefact that relies on the prior act of printing (and bibliography, microfilm, digitisation, transcription, to be sure). It will never represent what was not printed (and this will mean particular underprivileged Englishes are minimally visible).

There is another dimension of representativeness that matters for LDNA. Drawing on techniques from corpus linguistics makes us aware that in the past corpora, collections of texts produced in order to control the analysis of language-in-use, were compiled with considerable attention to the sampling and weighting of different text types. Those using them could be confident about what was in there (journalism? speech? novels?). Do we need that kind of familiarity to work confidently with EEBO-TCP? The question is great enough to warrant a separate post!

The points raised so far have focused on the whole of EEBO. There is an additional challenge when we consider how well EEBO can represent the sixteenth century. Of the ca. 55 000 texts in EEBO-TCP, only 4826 (less than 10 per cent) represent works printed between 1500 and 1599. If we operate with a broader definition, the ‘long sixteenth century’ and impose the limits of the Short Title Catalogue, the period 1470-1640 constitutes less than 25 per cent of EEBO-TCP (12 537 works). And some of those will be in Latin and French!

Of course, some sixteenth century items may be long texts–and the bulging document count of the 1640s is down to the transcription of several thousand short pamphlets and tracts–so that the true weighting of long-sixteenth-century-TCP may be more than the document figures indicate. Yet the statistics are sufficient to suggest we proceed with caution. While one could legitimately posit that the universe of English discourse was itself smaller in the sixteenth century–given the presence of Latin as scholarly lingua franca–it is equally the case that the evidence has had longer to go missing.

As a first post on the theme, this only touches the surface of the discussion about representativeness and limits. Other observations jostle for attention. (For example, diachronic analysis of EEBO material is often dependent on metadata that privileges the printing date, though that may be quite different from the date of composition. A sample investigation of translate‘s associations immediately uncovered a fourteenth-century bible preface printed in the 1550s, exposed by the recurrence of Middle English forms “shulen” and “hadden”.) Articulating and exploring what EEBO represents is a task of some complexity. Thank goodness we’ve another 20 months to achieve it!

* Read the full Linguistic DNA review here. The e-edition of Bruni & Pettegree’s volume became open access in 2018.