This blog post excerpts material Iona wrote reflecting back on her contribution to the SHARP conference in Paris in July 2016, building on the work of her PhD thesis and incorporating material and processes that have formed part of the Linguistic DNA project. The full post can be found on Iona’s personal blog.

In preparation for the paper, I dedicated time to manually extract, compile and refine measurements for some of the early outputs from the LDNA processor. To fit in with the pledges of my abstract, I targeted the associations of valour and valiant in subsets of EEBO-TCP.

During my PhD, I used EEBO-TCP to provide context for my work with early modern bibles. Valour entered the equation as I examined trends in the translation of a Hebrew collocation gibbor chayil. In the King James Version (publ. 1611) most gibbor chayil men are “mighty . . . of valour”. The repetition of this phrase across the translation means that English bible readers could form associations between the group of characters referred to, in a similar manner to those who encounter the Hebrew narrative directly. For this to happen in translation shows that the translators recognised and (sometimes) prioritised the transmission of this connection; in this respect “mighty of valour” is a partial example of a larger trend in favour of a more technical approach to translation, a move likely influenced by the increasing use of precise cross-referencing in bible reading (facilitated by the introduction of verse numbers throughout the Bible, an innovation of the 1550s). Yet the phrase is intrinsically interesting because before that “valour” was not part of the English biblical lexicon.

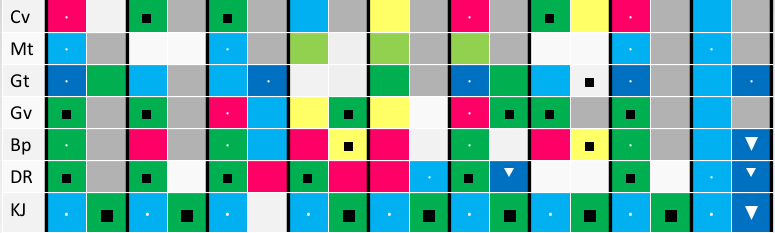

Collating instances of gibbor chayil demonstrates that the lexically related “valiant” was used in earlier translations, but in a piecemeal manner (illustrated by the changing distribution of black square bullets in the diagram below).

This diagram, extracted from my SHARP presentation, is one of a series colour-coded to highlight consistency within individual versions with a focus on the characterisation of Boaz. The black square bullets are added to highlight where a form of ‘valiant’ (or for KJ ‘valour’) was used.

By exploring the words valiant and valour with the LDNA tools, I was able to corroborate the impression I had formed during my earlier quantitative and qualitative analysis which was conducted via a standard EEBO-TCP interface.

The PhD bit

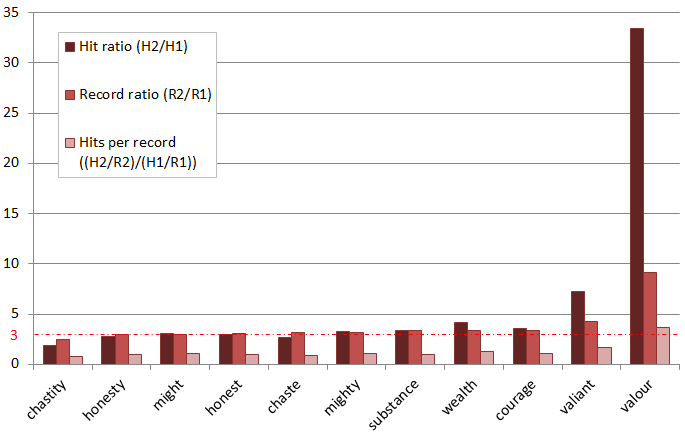

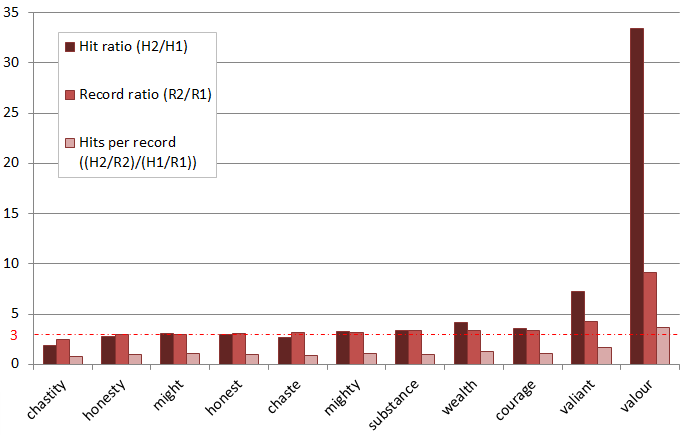

Searching hits in the population for the first century of English print (to 1570) and comparing that with the next half century (a collection of documents three times the size) I had observed that the frequency of both valiant and valour increased markedly above expectation.

Comparison of word frequency (hits) and distribution (records, hits per record) in EEBO-TCP for 1473-1570 (P1) and 1571-1620 (P2) expressed in ratios.

Scrutinising the data by decade exposed some significant textual influences. To quote from my thesis:

87 per cent of occurrences of “valiant” in the corpus for 1520-1529 (316 of a total 363) appear in a two-volume translation of the French chronicles of Froissart, while two other translated works account for a further 9 per cent; just 4 per cent of hits occur in ‘indigenous’ texts.

For “valour”,

a jump in the decade 1570-1579 is significantly related to the publication in 1579 of a translation from Italian: 403 of the decade’s 501 hits appear in a one-volume translation of The historie of Guicciardin conteining the vvarres of Italie and other partes (London, 1559). Once such scrutiny is imposed, it becomes evident that translation had a significant role in the increased currency of these two Latinate terms. It is also evident that the words normally appear in certain genres: conduct books concerned with warfare and chivalric behaviour; and chronicles of past history. This contributes to the recognisable sense of valour as “The quality of mind which enables a person to face danger with boldness or firmness; courage or bravery, esp. as shown in warfare or conflict; valiancy, prowess.”[ OED s.v. “valour|valor, n.”, §1c.] This sense, cultivated through translation in the course of the sixteenth-century, fits the context in which King James’ translators employ the word.

The LDNA bit

The subsets of EEBO-TCP sent through the LDNA processor earlier in the year were intentionally compatible with the periodisation of my thesis, providing windows onto English discourse that could be cross-referenced with the publication of particular bibles. The subsets thus incorporate all transcribed material from EEBO (TCP update 2015) known to have been printed during the following spans:

- 1520-1539 (cf. Coverdale Bible 1535, Matthew Bible 1537, Great Bible 1539)

- 1550-1559 (Geneva Bible 1560, Bishops Bible 1568); and

- 1610-1611 (Douai Old Testament 1609-10, King James Version 1611).

Taking the first and last of these, measuring PMI in windows of discourse around the word “valour”, we find marked change in the prominent associations. Our approach yields plentiful data, and we are still thinking through the challenges of visualisation. In the slide shown, I have coloured associated terms according to the innermost window in which the cooccurring lemma rises to prominence. Thus red terms occur frequently in the narrowest window around valour (+/-1 words), orange terms in the expanded window (+/-10 words) that might approximate the surrounding sentence, green for +/-50 words (which now form the default window size in our public interface) and blue for the wide discursive window of +/-100 words. (Many lemmas appear in more than one window, and the list shown for the later period does not reach to some relevant low frequency items such as “prowess”.)

What should be visible is a distinction between the use of “valour” as a synonym of value or worth (prominent in the 1520-1539 subset), and the association with conduct in conflict (dominant in the 1610-1611 dataset). Both senses were part of the Latin root “valeo” and, had King James’ translators ventured it, both could have been played upon to make even more “mighty men of valour” in 1611. (One of the exceptions comes at 2 Kings 15:20, where Menachem taxes all gibbor chayil men, “mighty men of wealth” in the KJV.)

Inevitably, the set of observations I could draw from this investigation are not part of the bottom-up process that LDNA strives to achieve. But the exercise has helped me to think through some different ways we will want to be able to interrogate our data and to study the effects of some different baselines for our expectation calculations. And it demonstrates, I think, the valour of conducting semantic enquiries through discursive windows.

_____

Notes

Thesis quotations are from: I. C. Hine, “Englishing the Bible in early modern Europe: The case of Ruth”, PhD thesis (University of Sheffield, 2014), p. 163. These numbers reflect searches conducted through the Chadwyck EEBO interface using its variant spelling option.

The datasets employed in my thesis are not quite identical to those used by the project: LDNA uses a slightly expanded version of the EEBO-TCP collection (last updated early 2015) with its spelling regularised and tokens lemmatised locally using MorphAdorner.