In December 2017, Sheffield MA student Nathaniel Dziura attended part of the Genealogies of Knowledge conference in Manchester. While the LDNA team were exchanging conceptual insights with other data-driven scholars, Nathaniel participated in sessions connected to a different field of interest. He writes:

As a member of the LGBTQ+ community, I am keen to contribute to research on how social factors impact language use, particularly gender and sexuality. As a second-generation Polish immigrant, raised with influence from both Polish and English culture, I am also very interested in the effect cultural background can have on the production of linguistic features.

Next year, I hope to start a PhD focused on this interplay between social and linguistic elements. Schumann (1978) suggested that the degree of ‘acculturation’ influences use of non-standard variants in second language learners. In other words, if the speaker is more immersed in the culture of their second language, they will be more likely to acquire native speaker-like linguistic variation. However, previous studies have not considered how other social factors such as sexuality might affect which features are acquired. This is despite previous studies having shown certain linguistic features to be cross-culturally associated with LGBTQ+ membership. These features include fronted-/s/ (Levon, 2006; Pharao et al., 2014) – colloquially stereotyped as the ‘gay lisp’ – and creaky-voice (Zimman, 2013: 3) – speaking with a low elongated ‘creak’, like a stereotypical ‘valley girl’. LGBTQ+ people do not inherently use these features, but they can play an important part in interaction (Barrett, 2017: 9).

I want to help fill this gap in the research by investigating how sexuality might affect the linguistic variants acquired in English by second language speakers (specifically, Polish migrants to England). I will examine whether the use of these features differs depending on two variables: the level of integration into British culture. And the level of involvement with the LGBTQ+ community.

This was the project I had in mind as I headed to Manchester for the conference. I was rewarded by an excellent thematic session on ‘Translation, Gender, Sexuality’.

I found Przemysław Uściński and Agnieszka Pantuchowicz’s presentations to be pertinent and insightful. Uściński’s talk focused on the downfalls with approaching Queer Theory in Poland from a ‘Western perspective’. The political environments in Poland and England have differed historically, and continue to do so. Uściński argues that ‘LGBT emancipation’ has not yet occurred in Poland. Critical theorisations of gender are intentionally scarce in Polish academic discourse. The reception of Queer Theory in academia has been comparatively belated, and has sometimes discredited the LGBTQ+ movement. British society has its share of problems with LGBTQ+-phobia. Yet, Poland has seen much far-right and religious rejection of the LGBTQ+ community. These groups have dismissed LGBTQ+ identities as ‘Western secular propaganda’ and ‘gender ideology’. So, English translations of concepts within Queer Theory, which are gradually being introduced to Polish academic works, reflect English notions and societal progress. Even when concepts from Queer Theory enter Polish, there is no possibility for their dissemination within Polish society. Queer Theory tends to be viewed as a ‘foreign’ and subversive concept. A theoretical importation into Polish from English, and not one congruous with Polish culture.

In another paper, Pauline Henry-Tierney noted that misinterpretations in translation of Beauvoir’s ‘Mauvaise Foi’ have slowed academic progress on the subject. Taking this into account, perhaps misinterpretations of Queer Theory as a ‘foreign’ concept to Poland are hindering the normalisation of LGBTQ+ concepts and perpetuate their perception as something radical and provocative.

This thematic session highlighted that introducing concepts into a language through translation can be a step towards spreading those ideas within another culture. However, this alone might not be enough to achieve society’s understanding and acceptance of those concepts. The translation of Queer Theory between cultures was not an issue I had previously considered. This thematic session reinforced that the political and social environments in Polish and English culture exhibit stark differences. This is significant within the framework of acculturation: LGBTQ+ community membership is arguably more accepted in British culture, and consequently so are associated non-standard language features. So one might predict that LGBTQ+ Polish migrants to England who become more British-acculturated are more likely to produce non-standard features associated with LGBTQ+-community membership than those who are less British-acculturated.

Overall, I was able to interact with academics from areas such as translation studies and politics with whom I would not otherwise be able to network. I am very grateful to the Linguistic DNA team for inviting me to attend the conference. The insights it has given me will be useful in my academic pursuits!

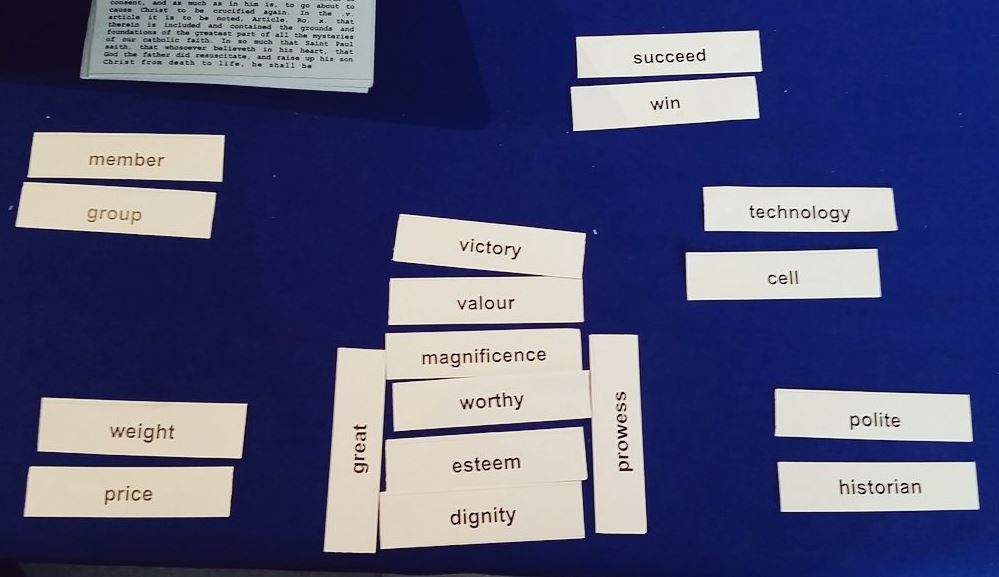

Featured image:

Jaap Verheul (Utrecht) presents an example from ShiCo research at the Genealogies of Knowledge conference, 8 December. Photo (c) I.C. Hine.

References:

Barrett, R. (2017) From Drag Queens to Leathermen: Language, Gender, and Gay Male Subcultures (Studies in Language Gender and Sexuality) Oxford: Oxford University Press

Henry-Tierney, P. (2017) ‘Translating in ‘Bad Faith’? Articulations of Beauvoir’s ‘Mauvaise Foi’ in English’, Genealogies of Knowledge I: Translating Political and Scientific Thought across Time and Space, Manchester: University of Manchester

Levon, E. (2006) ‘HEARING “GAY”: PROSODY, INTERPRETATION, AND THE AFFECTIVE JUDGMENTS OF MEN’S SPEECH’ American Speech 81 (1): 56–78

Pantuchowicz, A. (2017) ‘Translation and the Failure of Gender Mainstreaming in Poland’ Genealogies of Knowledge I: Translating Political and Scientific Thought across Time and Space, Manchester: University of Manchester

Pharao, N., M. Maegaard, J. S. Møller & T. Kristiansen (2014) ‘Indexical meanings of [s] among Copenhagen youth: Social perception of a phonetic variant in different prosodic contexts’ Language in Society 43, 1–31

Schumann, J. H. (1986). Research on the acculturation model for second language acquisition. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 7, 379-392

Uściński, P. (2017) ‘Thinking Sexuality/Translating Politics: Queerness in(to) Polish’ Genealogies of Knowledge I: Translating Political and Scientific Thought across Time and Space, Manchester: University of Manchester

Zimman, L. (2013) ‘Hegemonic masculinity and the variability of gay-sounding speech: The perceived sexuality of transgender men’ Journal of Language & Sexuality 2 (1): 1-39

Seth and Iona present a joint paper with LDNA data at Genealogies of Knowledge. Photos (c) Japp Verheul.

It is Writing as Resistance.

It is Writing as Resistance.