Knowledge, truth and expertise: experiments with Early English Books Online

Wondering what Linguistic DNA is bringing to the Society for Renaissance Studies? Here are the abstracts for two panels of papers, and information about our hands-on demonstration session (drop in).

United by a common interest in data-driven approaches to meaning and a focus on the transcribed portions of Early English Books Online (EEBO-TCP), this interdisciplinary panel brings together new research from the Linguistic DNA project and the Cambridge Concept Lab.

What is EEBO anyway? Contextual study of a universe in print

Iona Hine and Susan Fitzmaurice (University of Sheffield)

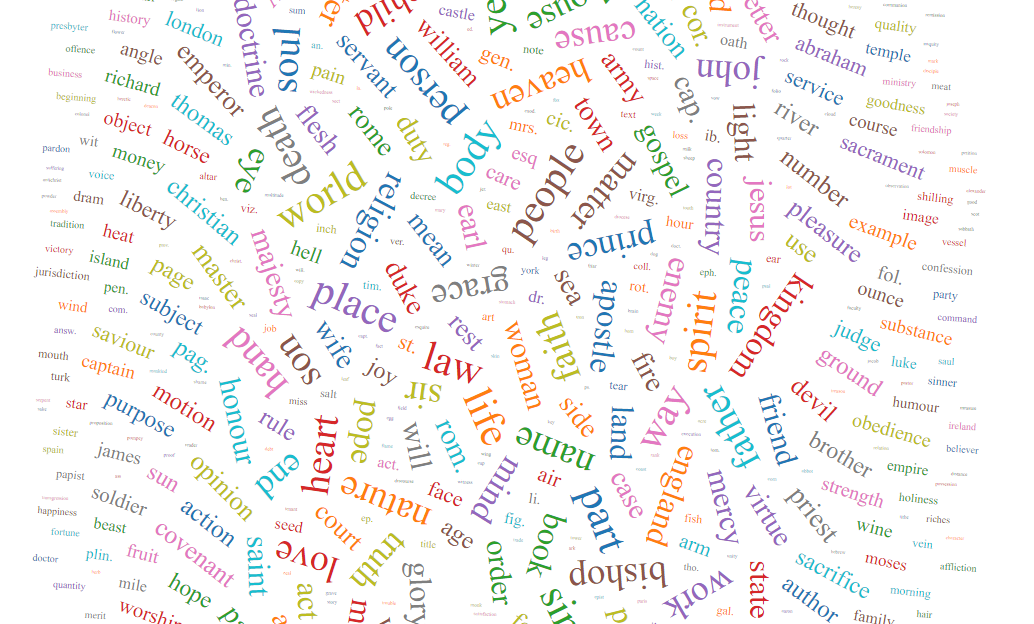

Since 2015, the Linguistic DNA team has been developing methods for mapping meaning and change-in-meaning in Early Modern English. Our work begins with the hypothesis that meanings are not equivalent with words, and can be invoked in many different ways. For example, when Early Modern writers discuss processes of democracy, there is no guarantee they will also employ a keyword such as democracy. We adopt a data-driven approach, using measures of frequency and proximity to track associations between words in texts over time. Strong patterns of co-occurrence between words allow us to build groups of words that collectively represent meanings-in-context (textual and historical). We term these groups “discursive concepts”.

The task of modelling discursive concepts in textual data has been absorbing and challenging, both theoretically and practically. Our main dataset, transcriptions of texts from Early English Books Online (EEBO-TCP), contains more than 50 000 texts. These include 9000 single-page broadsheets and 162 volumes that span more than 1000 pages. There are 127 items printed pre-1500, and nearly 7000 from the 1690s. The process of analysis therefore requires us to think carefully about how best to control and report on this variation in data distribution.

One particular question that has arisen affects all who attempt to use EEBO: what is in it? To what extent is its material from pre-1500 similar in kind (genre, immediacy, etc.) to that of the messy 1550s (as the English throne shifted speedily between Edward VI and his siblings), the 1610s (era of Shakespeare and the King James Version), or the 1640s (when Civil War raged)? This paper is a sustained reflection on attempts to find out “What’s in EEBO?”

In the beginning was the word?

EEBO-TCP and another universe of meaning

Seth Mehl (University of Sheffield)

When a new idea is conceived, how does it find expression in language? Between 1450 and 1750, the English lexicon expanded dramatically, and literary scholars, philologists, linguists, and historians have sought to document and demonstrate the paths taken by key social and cultural vocabulary, charting the history of what would become key social and cultural ideas, discourses, and concepts. In such cases, the topic and language for investigation has been intuited on the basis of extended qualitative reading, and the objects of investigation tend to be individual words. With the advent of a searchable database of early modern texts, such intuitions can be tested at scale, and the initial object of inquiry can shift from individual words to relationships between sets of words.

What happens when we invert the traditional process, taking the thousands of texts digitised in EEBO-TCP and applying computational techniques to model language change independent of human intuition? Can such techniques indicate meaningful relationships between key words that human researchers had not intuited or observed? To what extent do observations founded on over 1 billion words of early modern English correspond to and diverge from what scholarly readers have already inferred? Is it possible to identify discourses around key ideas even when the apparently related key words are absent? Combining insights from the Keywords Project with tools developed by the Linguistic DNA project, this paper will explore how concept modelling can be applied to re-examine meaning in early modern texts.

Beyond Power Steering:

re-constituting structures of knowledge in 17th-century texts

John Regan (University of Cambridge)

One of the axioms of the Cambridge Concept Lab is that digital means of enquiry should provide qualitatively new kinds of knowledge, if we are to realise their full value. This is to say, that computation should not merely provide ‘power steering for the humanities’, but allow one to discover something different in kind about how knowledge was structured in the past.

Making good on this axiom necessitates judgements on the part of the user of digital technology about how to design one’s modes of address to (for example) natural language data sets such as Early English Books Online- TCP, in order that one is not only adding ‘power steering’ to existing, familiar types of enquiry. It also necessitates making decisions about when to come to rest at results (that is, when to cease enquiry); judgements of where digital data can be said to be producing discrete and unfamiliar forms of knowledge.

This paper will present tentative first signs of what the Cambridge Concept Lab believe are historically-discrete conceptual structures, based on data from the early seventeenth-century portion of EEBO-TCP. Two such structures will be described, one entitled ‘Mutual Dependence’, the other ‘Self-Consistency’. As will be shown, familiar forms of knowledge that are held and expressed in sentences and paragraphs, organised by grammar and understood by readers largely as explicit sense, may be contrasted with this evidence of qualitatively different conceptual structures in the textual record. While this paper does not set out to debunk existing theories of the structuration of knowledge and its transmission in the seventeenth century as have become established through centuries of close reading, it does seek to enrich our understanding of these traditions by attending to conceptual, and not exclusively semantic, thematic or rhetorical, structures.

It appears uncontroversial to assert that concepts are determining with regard to features of language use such as explicit and implicit semantic fields, theme, word order, and syntactic relations at the level of the sentence. Nevertheless, recognising that concepts have lexical and semantic extension is not the same as accepting that the two are identical in kind. This paper’s claims about conceptual structure will be based upon evidence from the early decades of seventeenth-century data from EEBO-TCP.

Our afternoon panel is a little depleted (by ill-health) but features Jose M. Cree (Sheffield) on Neologisms and the English reformation, Lucas van der Deijl (Amsterdam) on The collaborative Dutch translations of Descartes by Jan Hendrik Glazemaker (1620-1682), and a little extra time for discussion.

DROP-IN SESSION

All SRS delegates are very welcome to drop in to our demo workshop, where we will be providing a 10-15-minute introduction to our tools (3:30pm, repeated at 4:30pm) and the opportunity for hands-on experimentation. This is in the Hicks Building, Floor G, room 29. (About 2 minutes walk from Jessop West, across the main road and a little uphill. Directions.)

Snapshot from campus map, featuring the Hicks Building.